Does it seem a farce to personify the world around us? The non-person world is going on all the time, just doing its myriad things. We share the same time and space coordinates as these non-person entities around us. We even share significant amounts of DNA with many of the organisms surrounding us. And yet, our brains are so composed to understand and shed light upon the mysterious that even this is not enough. We familiarize ourselves (literally: make like family) the non-person objects around us through figures of speech like personification and metaphorical language.

We say that the plate is sitting there on the table, but it’s not. It’s not sitting because sitting is a person’s verb. Sitting implies legs and hips and the option to stand if it pleases. The plate is definitely not sitting there, resting in the sun let in by the window. And the window isn’t letting in anything. It’s not because it can’t stop the sun from coming in either. Like a computer program, the window has no unplanned functions and cannot improvise outside of its design.

Some linguists say that humans, on average, employ 6 metaphors per minute of speech or writing. This includes both creative metaphors as well as “frozen” metaphors which are built into our language. In their book Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff, a linguist, and Mark Johnson, a philosopher, outline a variety of examples of metaphors hiding within and actively influencing the ways in which we perceive reality. Imagine, for example, the different conceptions of love under each of the following metaphorical structures: Love is a journey. Love is patient. Love is chemical. Love is war.

Consider similarly: Time is money; He shot down my argument; My thoughts are all over the place; etc. After a few examples the layered nature of language becomes a bit clearer.

It’s hard to imagine a world without metaphorical language to help us understand what is going on around us. Writer Edith Cobb wrote quite extensively about the nature of human imagination as a building tool and orientation factor among children. In her book, Ecology of Imagination in Childhood, she describes it thus:

“Children strive to fill the gap between themselves and the objects of desire with imagined forms. This psychological distance between self and universe and between self and progenitors is the locus in which the ecology of imagination in childhood has its origin.” (p.56)

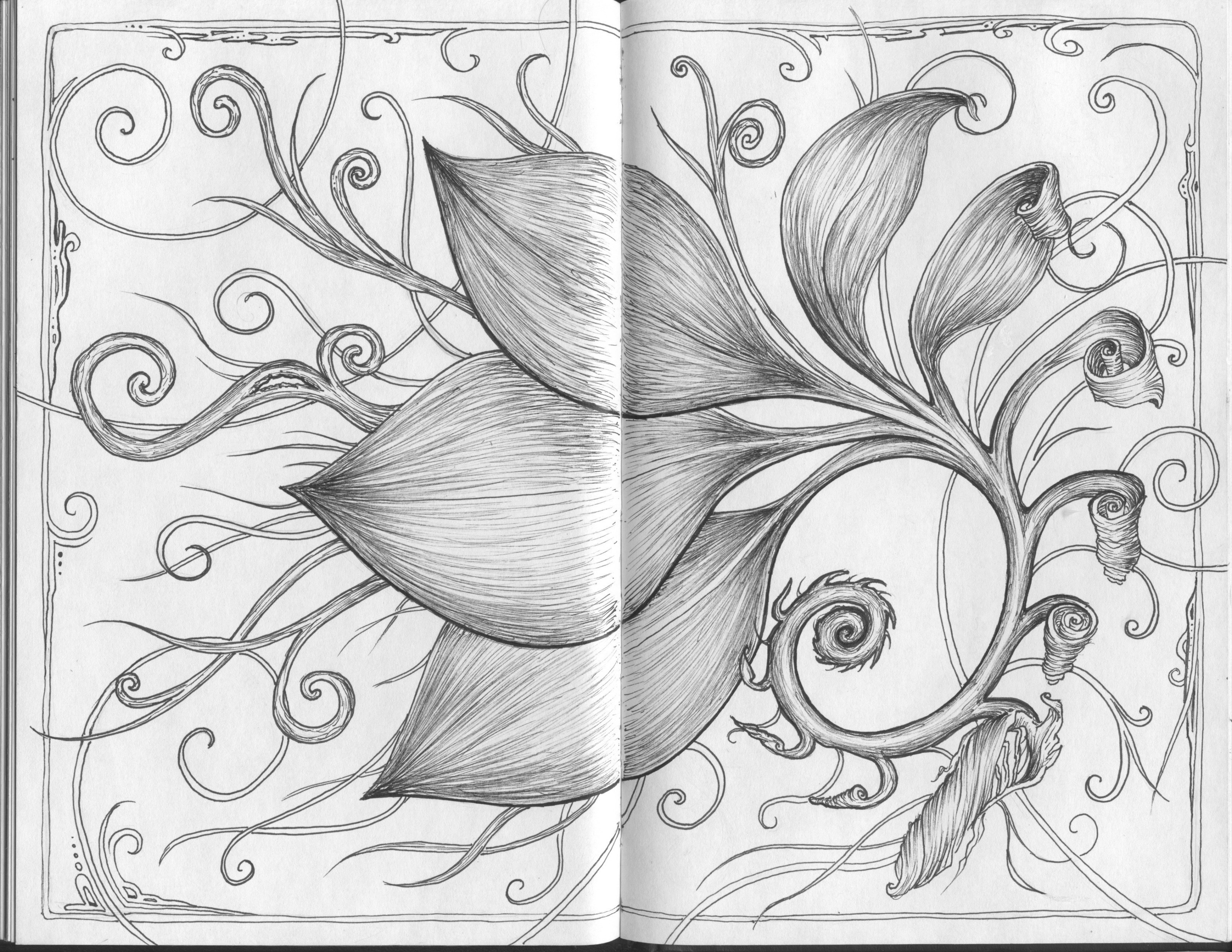

The “imagined forms” of personification and metaphorical thinking alter our finite comprehension of the world around us. If the trees can “clap” their “hands,” and we can clap our hands, here we have found a familiarity between an other and ourself. Here we have built a meaningful, imaginative bridge connecting and expanding our sense of self and filling in some of the holes in the map of our surroundings, making familiar the mysterious (and potentially threatening) unknown.

These other things around us, occupying this moment with us — how do we outright refuse the sense of their presence and participation in this space? There’s a constant story being told all around us, or perhaps a thousand narratives rubbing up against one another as within a great crowd, and each of us is the only witness in a unique theater.

Through metaphorical language and imagination, one reaches out into the abyss to find the object of desire (from Latin: “of the stars”). We return from our reaching to find something of that same dark matter inherent in our own souls, confirming or securing our kinship with the other. This relates and deepens the mystery, relieving one of the solitude, but not of the wonder. Similarly, the stillness of the plates and cups on the table somehow also speaks to that deceptively quiet abyss inside of all of us.

Video collage by Matt Wisiniewski

A breeze presents itself now and again outside, affecting everything from the cadence of the crickets to the trees and their thousand clapping hands. I live near the ocean and, as though in emulation, the wind often plays the trees like they were calm and distant, crashing waves. Over this, the breeze is luring in the salty air from the sea. Clapping and playing and luring, the non-person world requests an audience. And I being the only one in the theater, witness it.