Category: learning

Ink Drawing and a Note on Effortless Effort

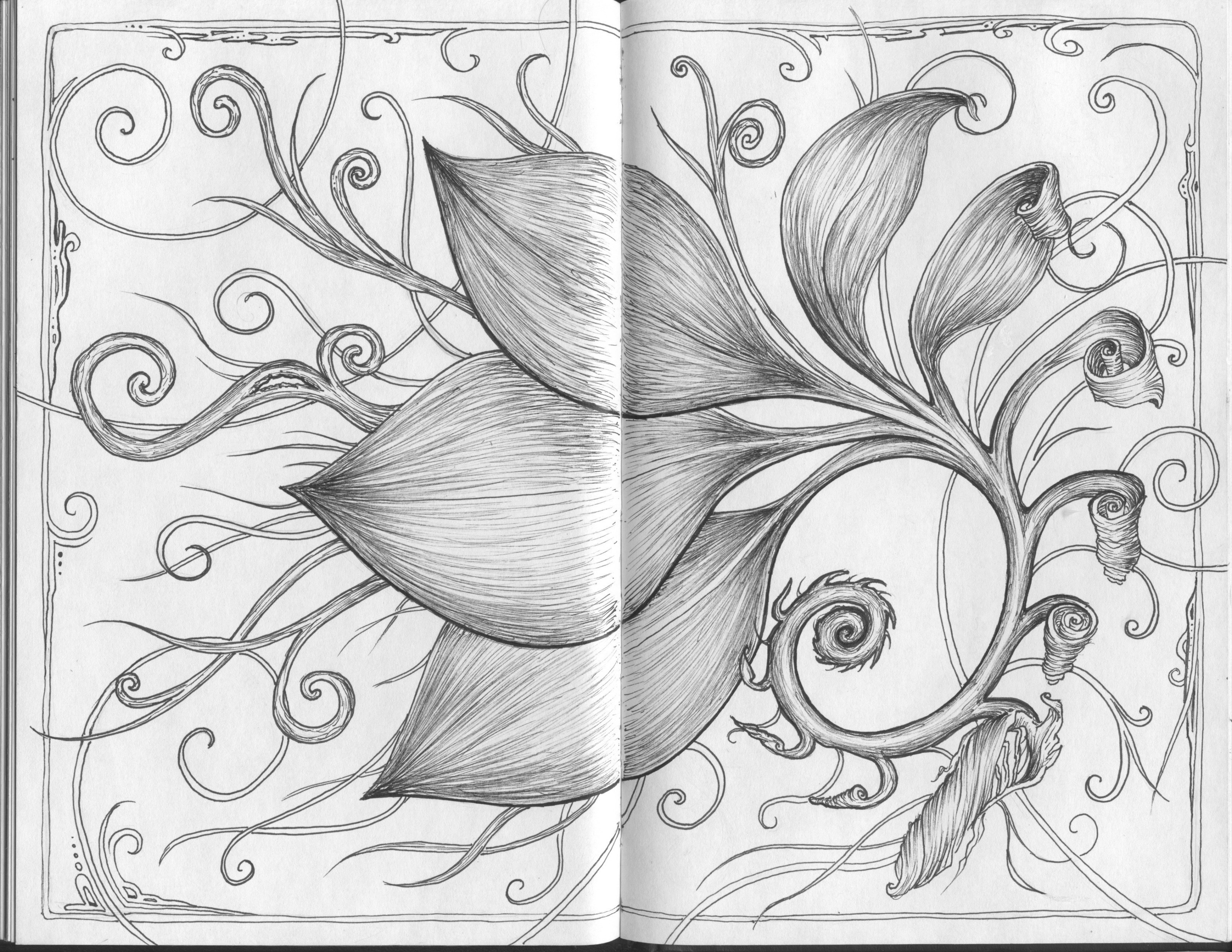

The titanic effort that we sometimes suspect is required for what we want–whether to calm our restless inner chatter, to attain peace, happiness, or motivation–is what prevents us from attaining it. Over the last couple of days, I have not been able to shake this image of a mother putting her infant to bed. An idea clings to the image: that the way she so carefully slides her arm out from beneath the infant’s back so as not to reawaken it embodies the way we might put forth effort and comport ourselves, the way we might adjust ourselves when we begin to lose hope, lose our sense of well-being, our sense of inner-outer balance, or our motivation. With a sense of trust. Without desperation. There is a thread of deep care running through the world, straight through us, but it is quiet and vanishes if grabbed at. Choosing to make my efforts simpler, like these stippled dots, little by little, is learning to trust the quieter instincts.

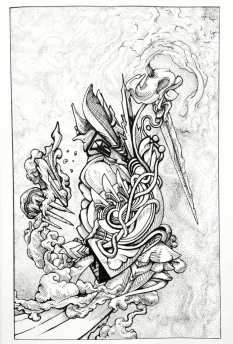

A student showed me this drawing looks like a heart surrounded by daggers. Jen says it has a crane thing going on.

Show, Don’t Tell: Using Biomimicry to Instill a Growth Mindset

“Show the readers everything, tell them nothing.” – Ernest Hemingway “In my view, nothing’s ever given away. I believe to advance that you must pay.” – Young Fathers

Imagine you are a teacher smitten with Carol Dweck’s idea that human thinking patterns can be put into two distinct categories when it comes to growth: fixed mindset and growth mindset. The first sees abilities as fixed, inborn; the second believes that their abilities can be cultivated. One of the central themes Dweck uses to distinguish the two perceptual frameworks is how we deal with failure. You want the students to get it in their nerves that failure is not just something they had best learn to accept: it is inevitable, necessary. You want to instill a growth mindset, to move people toward their potential rather than hold them in their helplessness, but you can feel the difficulty in making the case convincing. Likely, no great inner revolutions will be caused simply by telling students about the concepts. “Clarity, clarity, surely clarity is the most beautiful thing in the world,” George Oppen wrote. Perhaps a supremely clear conceptualization could inspire the consciousness necessary to initiate a blossoming of awareness; but then a few students will be daydreaming, a few others will be absent, and if you only tell them, only once, you will have already lost some of them. More likely, it will not be sufficient for transformation to rely solely on verbal communication. In fact, students are very sophisticated and actively engaged in posture detection. It is too easy to read the right books and too cheap to repeat what they say. Students want a teacher, not an actor, and a real teacher is one who actually houses the knowledge being imparted.

To show, the teacher must construct means to knowledge and transformation that have built into them the ideas they wish to impart. As an example, to show the concept of growth mindset, we could design a project based on the idea of biomimicry. If the idea of a helicopter’s mechanism for flight, its blades, can be seen as derivative of a maple seed, which by its subtle construction guarantees flight, a humbler, less overblown idea of human achievement could be adopted. Since the fixed mindset is founded on a common misunderstanding about how talent occurs in people (they just are that way), then exposure to examples of biomimicry could counter the false belief. In the same way that spectacular human inventions seem made by an elite of geniuses, each in a league of their own, the fixed mindset comes from the misbegotten notion that a given talent is a natural, prepossessed characteristic of the one exemplifying it (i.e. in a league of their own). The Oxford dictionary states that to “invent” is to “create or design (something that has not existed before); be the originator of.” We have the idea that inventors do their work “out of thin air.” Biomimicry challenges that definition. It suggests that many human inventions correspond to models in nature. If we wish to acquire or develop a talent, as students we need to exercise a similar challenge to the elitism that suggests we do not have what it takes. Such talents have doubtless been cultivated with long hours of practice by people who may now appear as gods, be treated as gods, and even live like gods, but they are, in the end, only people.

Below is the Young Fathers’ music video for “In My View” that came out this week (their much awaited album, Cocoa Sugar, due for release March 9). Filled with penetrative gazes, flashy costumes, mysterious conversations, and emotional upheavals, the viewer struggles to discern a unifying narrative. Then, at the 2:20 minute mark, the narrative comes together with a couple of words. Upaya in fine dress.Some Things Only Come Together In The End

Bridges of Play in Art, Philosophy, and Childhood

The nature of the will is one of the major problematics of life. Philosophers and artists have long labored to clarify the position we are in concerning the will. How much power does one person have? How much responsibility does one have in achieving for oneself the good life, and how can this be extended to others? How exactly are we situated in this world? To better understand the nature of will, artists, philosophers, and children open themselves up to opposition by treating it with a sense of play.

The child at play gives form to conflict, practicing “out in the open” in order to internalize what has been noticed in the external world, to gain understanding of self and situation. The forces driving conflicts between people are usually invisible, ideological, and unconscious, but once they are driving behavior, the child becomes aware yet lacks understanding. To develop a working model, or what Edith Cobb called a “world image,” the behavior is reproduced in experimental play.

Philosophers routinely reflect and do their thinking by surveying both sides of a problem. Socrates is the archetype for this. In his dialogues we often find Socrates asking questions normally thought to have obvious answers, questions like, “Do I want what is good?” As part of a chain of questions that bring the other’s inconsistencies of thought into higher resolution, he is surprisingly effective. Socrates often leaves his company in a state of shock from having lived so long under the aegis of certain beliefs and values without examining them.

Similarly, artists often present situations without explicitly taking a side. In crafting a story, an author takes all the time that’s required for viewers to believe and situate themselves in the whole driving conflict. In order to do this, they must give equal weight to opposing sides. Good is labored equally to evil. This cannot be understated. Evil is not run away from. The author must take a detached stance to good as well as evil, and the long process of crafting such a story is a redemptive process for the author, for in that time love has been taken to evil. The work is finished; now the conflict is felt by the reader, in all its natural complexity. And this is what the work offers that life tends not to: honor to the paradoxical complexity of living.

The feeling of conflict is not going to be novel for anyone. Life is difficult, long, a labyrinth. No map could ever be created that would give absolute lasting order to the world, whereby we could determine what to do or where to go next. What is unique to the arts is that they offer safe passage through experience, and thus to transformation. In other words, the arts offer the best simulacrum of such a map. Life is always giving us experience; too often we fail to travel through it. Whether from anxiety or what Kierkegaard called the “dizziness of freedom,” fear or sheer confusion, we seem resistant to understanding or processing what happens to us. Such resistance promotes undesirable thought and behavior loops. If we would travel through experience, our transformation would be the effect. In order to do this, we must sometimes come down from the clouds of our own cleverness and righteousness and ground ourselves in earthly silliness. There are many compatible modes of being. There is no going out of character. To quote Walt Whitman,

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Annie Dillard and Thomas Merton on Pushing Passed “Good Enough”

“Do not depend on the hope of results. You may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.” – Thomas Merton

A thousand times a year students ask me, “Is this good enough?” Their eyes gaze up at me from over a work of art that, yes probably, has hit all of the required standards, seeking some respite from the challenge set before them. Good enough? Compared to what? — I send the ball back into their court. In that moment, either they fold, laughing, and label it “good enough” for now, presumably to be improved upon someday, some other day; or a light flashes within them, a neurological bridge sparks, and they begin the journey of passing through the center of their own potential.

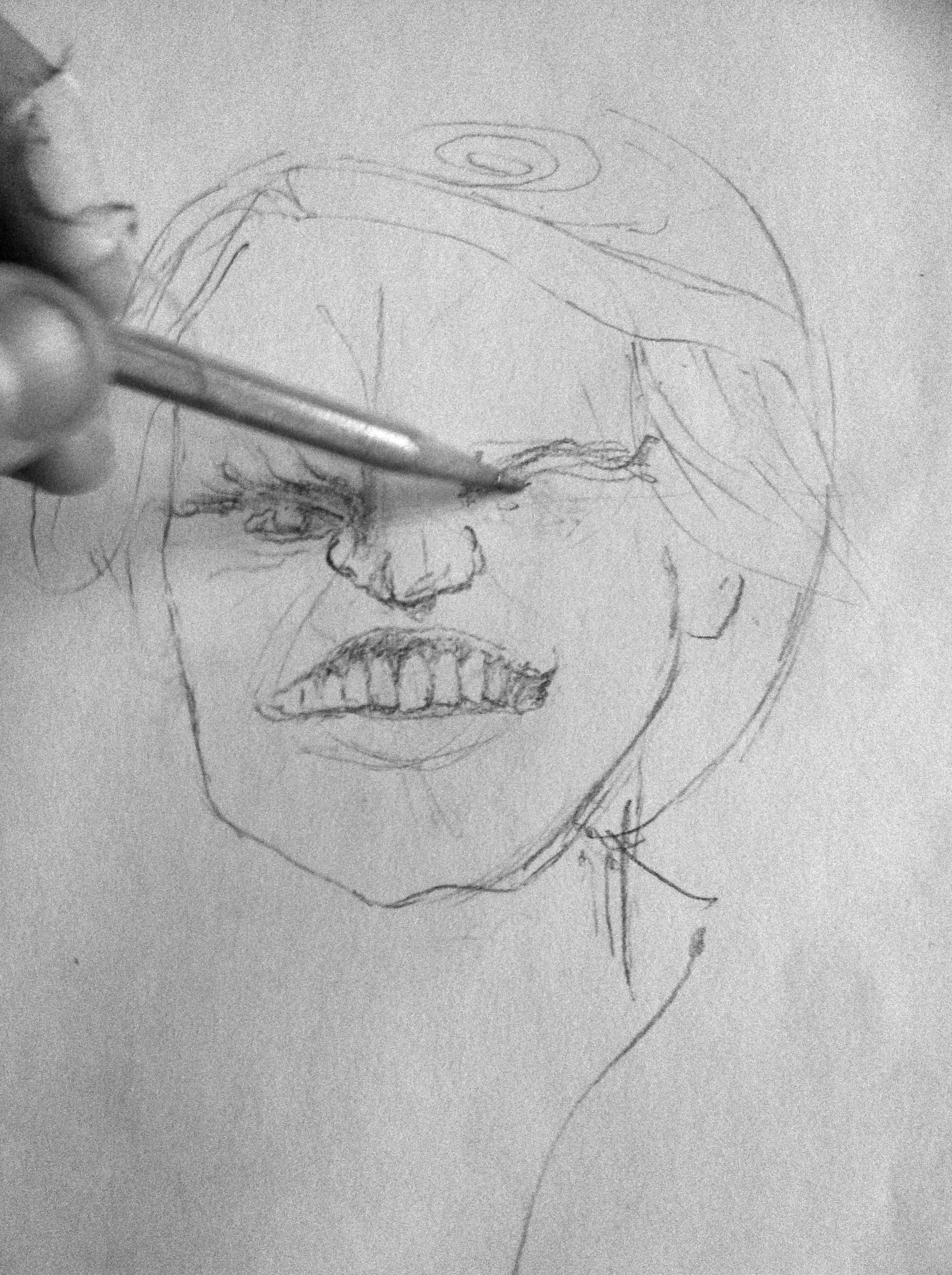

An essential idea that I live by and share with my students often is that a work of art must pass through a stage of imperfection, even awkwardness, on its way to something better. (Take, for example, this old caricature sketch of Carl Sagan by Zack.)

Born into a system of norms set strategically before us, it’s always surprising to be reminded that we are still ultimately at the helm of this process of what we accomplish and what we choose to bring into being.

We make sure our jobs are good enough to pay the bills, our health is good enough to get us through our days, our relationships are good enough that we can all get by without killing each other. But isn’t it true that often we don’t take the opportunities to make these things more meaningful, more able to feed our spirits and raise that bar that has been set for us? Have we any idea what’s possible?

The poetically irreverent American novelist, Tom Robbins, once wrote: “we waste time looking for the perfect lover instead of creating the perfect love.” This is a reminder that our relationships, our jobs, our daily interactions are creative acts. We must create the world we seek or else settle for a world designed by someone else for someone else’s vision of what is possible. Our north star then is to find what moves us to raise our bars and push passed the point of “good enough” towards our definition of sublime. The brave and brilliant American writer Annie Dillard put it this way:

“There is always the temptation in life to diddle around making itsy-bitsy friends and meals and journeys for years on end. It is all so self conscious, so apparently moral…But I won’t have it. The world is wilder than that in all directions, more dangerous…more extravagant and bright. We are…raising tomatoes when we should be raising Cain, or Lazarus.”

At a certain point, we have to ask: Are we aiming to settle for what the world has asked us to achieve, or do we see the potential for something radically more meaningful? The first story has already been told. The second is the story that you may have been born to tell.

The challenge of refining a work of art — and that may be the art of painting or of teaching, of building relationships or being a better or more authentic communicator — is complex to say the least. Realist painter Jacob Collins said that this process “…is torture… There’s always some newly seen flaw. But the little glimpses of beauty between the anxiety make it worth it.” You can tell when your work is definitely not done, but by working on it, you also run the risk of overworking it. And in the back of your mind, you know there is the very real possibility that your work may fail or be noticed by none. On this Thomas Merton wrote:

“Do not depend on the hope of results. You may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.”

Annie Dillard and Thomas Merton are two twentieth century writers, working somewhere between spiritual pilgrims and fringe revolutionists, who spent their lives conjuring and stoking this devotional fire dedicated to telling a different story of being human in our modern world. They found quickly that to do this one must abandon the temporary comforts of seeking affirmation and instead follow with steadfastness the vision of human potential that haunts their hearts like a calling.

The act of pushing passed our inherited story of “good enough” is nothing short of a miracle. It’s the task of taking the antiquated, inherited definitions of “commitment” and “devotion” and “faith” and “beauty” and reclaiming them, covering them in graffiti, in your very blood, and letting them help you bring your vision of your great works passed product straight into the heart of the process. Annie Dillard put it this way:

“One of the things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.”

The Disembodiment of Knowledge

Thinking about Media with Socrates and McLuhan

“Everybody experiences far more than he understands. Yet it is experience, rather than understanding, that influences behavior.” – Marshall McLuhan

A gradual externalization of human knowledge began with the advent of written language, the first alphabets arising around the 3rd millennium BC, and the old Latin alphabet around the 2nd century BC. Invented smack in the middle of a world thriving on oral traditions, alphabets gave humans a revolutionary tool for sharing and preserving information, knowledge, and wisdom. This new vehicle for human thought seriously influenced not just how we communicated and documented our world, but it changed the ways that we understand and respond to reality. The brilliant and prolific writer, Marshall McLuhan, known best for his memorable statement “the medium is the message,” commented on how the invention of writing laid the foundation for our modern mode of thinking:

“Western history was shaped for some three thousand years by the introduction of the phonetic [alphabet] .… Rationality and logic came to depend on the presentation of connected and sequential facts or concepts.”

The advent of writing also relieved individuals of what was likely an ongoing and challenging task—that of memorizing and internalizing all of their stories, myths, rituals, poetry, recipes, and inter-generational knowledge. What once only travelled by means of memory and the tongue, now could be written down and spread across great distances, enduring the test of time with acutely consistent messages. Socrates spoke of this transition, and Plato wrote of it. However, these two thinkers were not quite so keen on the convenience of writing, but rather wary of its effects on man.

“If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls; they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks. What you have discovered is a recipe not for memory, but for reminder.”

In Plato’s writing entitled Phaedrus, Socrates claimed that his true teachings would never in fact be transposed into writing, but spoken only. So, can we say that we know anything of (the already very elusive) Socrates? He feared the disembodiment of learning which he believed came with writing, including the loss of context, intonation, and response. Still, it proceeded thus onward with the invention of the printing press, the telegraph, the photograph, and so on to the virtual age, each technological medium bringing with it great strides for the collective human thought-pool.

With such elaborate conveniences, however, one must wonder which muscles of ours have been allowed to rest, and to what atrophy?

Living alongside the Internet, for example, we today need remember little because Google will always recall it for us at a moment’s notice. Nothing need be internalized or set to memory because it’s already stored in the mind of the global village, in the external memory of our collective consciousness. McLuhan, who referred to these inventions as extension of man — a reaching outward, beyond oneself. He was aware of and wary of this disembodiment, and yet he knew that this was the direction into which humans would need and choose to venture. (And indeed we have–from living through online avatars, to visiting art museums via robots, to the Voyager space probes–humanity has created a multitude of extensions of our selves and species which enable us to reach further and with greater and more creative facility out into the universe.)

We expand adventurously outward into the universe with our tools as our tightropes. Alan Watts once said that we “…are a focal point where the universe is becoming conscious of itself.” From this perspective, our man-made extensions only reveal an ongoing natural progression of extensions and connectedness between us and the universe. Whitman, in his epic Song of Myself reminded us that we are “not contain’d between [our] hat and boots.”

Still, what other effects are included in this abundance of extensions? Socrates went on to describe the burden of too much information:

“And it is no true wisdom that you offer your disciples, but only its semblance, for by telling them of many things without teaching them you will make them seem to know much, while for the most part they know nothing, and as men filled, not with wisdom but with the conceit of wisdom, they will be a burden to their fellows.”

Many of us have so little time today to spend in quality research of a topic in order to really understand it. So we trust various news sources, reporters, writers, or journalists to garner for us information synthesized into an understanding. And this sates many of our hunger pains or the social pressures to stay “informed.” Yet these are second hand opinions, often from perspectives containing ulterior motives. If we are seeking to learn online, the distractions alone can turn many sincere pursuits of knowledge into scenarios of kids in candy stores.

So, how we learn about the world around us is a tricky and mysterious process. We learn whether or not we intend to. One thing is certain, as McLuhan points out:

“Everybody experiences far more than he understands. Yet it is experience, rather than understanding, that influences behavior.”

Education specialists suggest that educators and learners need to bridge the gap between theory and practice—that is, to practice what is referred to as Experience Based Education. We need more opportunities to practice and have experiences with a body of knowledge in order to effectively transform it into useful insight or wisdom. We must embody it: try it on, touch it, maneuver it. If we try to build knowledge with bits of information which are housed—to varying degrees—outside our heads and out of our hands, it becomes significantly harder to synthesize these bits into meaningful, larger ideas, projects, or movements.

This synthesis produces all of humanity’s great emergent art forms and includes the alchemy necessary for making meaning in, improving, and contributing to our world. Maria Popova, an articulator of interdisciplinary thought and a prolific author, writes:

“In order for us to truly create and contribute to the world, we have to be able to connect countless dots, to cross-pollinate ideas from a wealth of disciplines, to combine and recombine these pieces and build new castles.”

Our memories and experiences are qualitative and exponential “castles” which continuously build upon themselves. Though it’s wonderfully exciting to live vicariously through film and sitcom and bloggers and vloggers, it is essential to remember that they cannot earn for us our experience or or make for us our art. And though it is convenient to allow our technology to temporarily remember for us our stories, recipes, quotes, and poems, we must keep in mind that it cannot earn for us our wisdom.

Showing Promise

A student puts off his final essay till the night before it’s due. The stakes are high. Four pages and 10% of his final grade for the course are on the line. The deadline looms guillotine-like above his head, and this motivates him. He gets his grade back soon and proclaims to his peers, “I don’t know how I got a 95% on my paper; I pulled it out of my butt the night before!” What’s notable about this common scenario, putting aside his rectal storage site, is that this 95% is viewed as a major shortcoming of the teacher and a buckling of the high standard of quality he or she is known or supposed to maintain.

Let’s assume for the moment that while this is true, it is not entirely true. Perhaps a second reading of the situation would ask, Why is the student not more impressed by himself, his transcendent nature, and what he was able to do with a few long, intense hours of focused, guillotine-dreading time? He has produced not just passable work; the work is good. It shows PROMISE.

We say of someone showing potential that he shows promise, exhibiting an aptitude or skill early in its flowering. Why do we use the word “promise”? Because, however nascent in its development, the potential culmination of the skill is perceptible. Because, like promising something will come to pass, those who show promise would lift themselves above their current orbit merely by staying their present course. Every person is a becoming, but that person who shows promise in a given capacity can consider himself promised a privileged position, a sacred earning, a gift, a power, merely by holding to the path along which he already finds himself. This is special, for noticing the path means already some part of the conflict about life has been overcome. A unifying direction has become visible from the chaos, a means to trump entropy, to “contribute a verse.” As Walt Whitman wrote:

O me! O life! of the questions of these recurring,

Of the endless trains of the faithless, of cities fill’d with the foolish,

Of myself forever reproaching myself, (for who more foolish than I, and who more faithless?)

Of eyes that vainly crave the light, of the objects mean, of the struggle ever renew’d,

Of the poor results of all, of the plodding and sordid crowds I see around me,

Of the empty and useless years of the rest, with the rest me intertwined,

The question, O me! so sad, recurring—What good amid these, O me, O life?Answer:

That you are here—that life exists and identity,

That the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.

Trusting the Ground of Learning

In order to access that “world in a grain of sand” which William Blake wrote about, physically, nothing more is required than to walk the beach, sit and comb the sand. In the end, physically, there is probably nothing required. What he meant was a psychological alignment. Only we think the weight of “infinity in the palm of the hand” is too great to bear alone, or it seems cheap, so we hire all kinds of help and conspire to lift the entire beach to see what’s holding it up. If we can do it together, after all our labors, then, maybe, the reward will be great. But a single grain of sand—there has got to be more to it than that. We’re not used to finding greatness without great expenditure.

Martin Luther King, Jr. once said in a speech that, to be concerned for others, we must “project the I into the thou.” The only way to test something truly is to test it on its own ground, to walk that ground in those shoes. This in itself is challenging enough; but it is impossible if one does not “know oneself” first. So the reverse is just as true. Nietzsche knew this well when he said, “The you is older than the I; the you has been pronounced holy, but not yet the I: so man crowds toward his neighbor” (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 60).