Category: sketchbook drawing

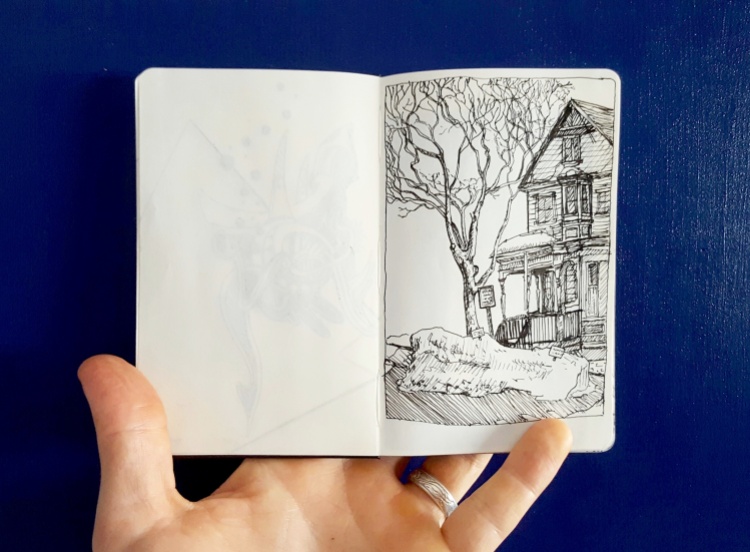

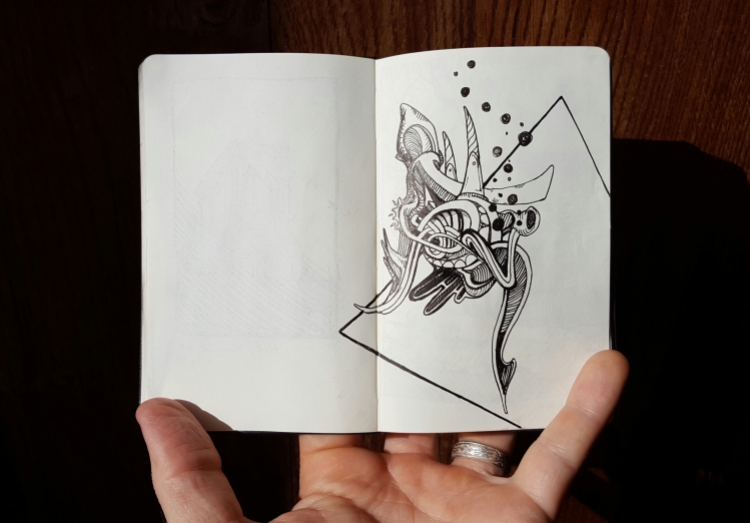

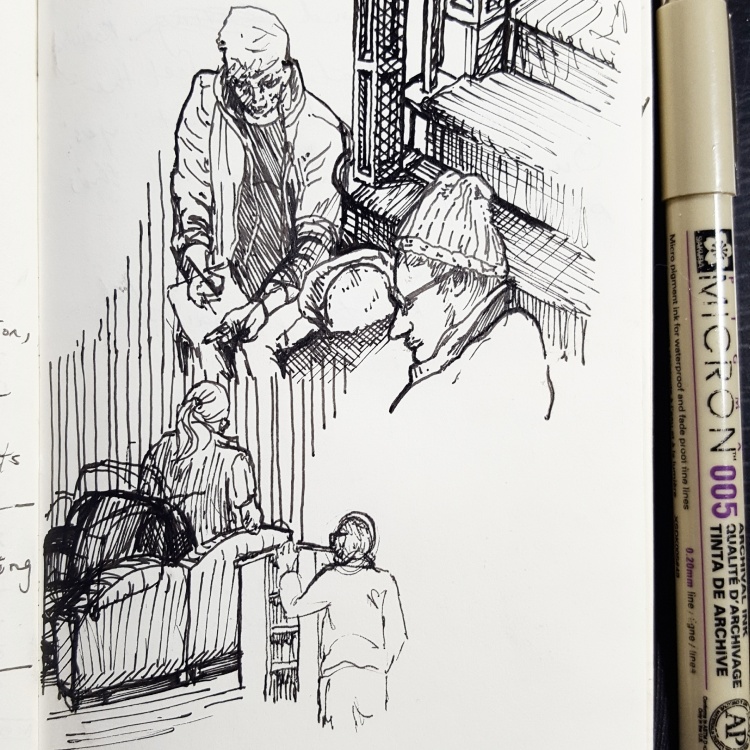

A Few Pages from Zack’s Small 2017 Sketchbook

In the Name of Marriage, Play!

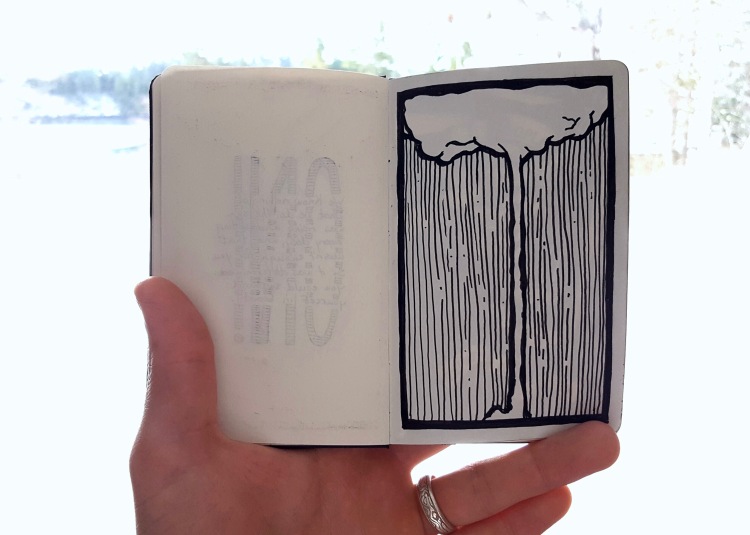

Turbulence Study at Salmon Run

It’s the time of year for the salmon to return to their birth sites. It was the first time I ever witnessed this–hundreds of salmon waiting to climb upstream to lay eggs, I am told, at the very same place they were born. Their long return from the ocean is a daunting thought. Then they get to fresh water and have to hurl themselves upstream! And this marks the end of a salmon’s life. Many, if not all, of the fish have stopped eating and are losing their scales and their color. I spent the day at Tumwater falls, watching them move upstream, attempting massive leaps against all odds (at one section I watched dozens of attempts and none made it).

I thought of Da Vinci’s turbulence studies and, perhaps in the same spirit as the salmon, wanted to challenge my limits, so I made my own study. Capturing the power of fast moving water is one of the most difficult things to daw: very ghostly, always vanishing from sight, somehow always different and always the same. My efforts were encouraged by studying the foam that had formed on top of the water, which aided in seeing the mostly invisible crashing and momentum of the river.

Stirrings of a 3rd Album & Sketchbook Doodle | Road Trip 9

Someone at the Door | Road Trip 6

Chasing Clouds | Road Trip 2

What Writing and Drawing Have in Common

Sometimes I pick up a book, only half intent to read it. I carry it with me. It is now a moving body, it seems, with a mind of its own, for I leave it in places and don’t know why. I lose sight of it, become half aware of it or forget about it completely. If it travels far enough, it ends up on the bedside table, and there I wait for an artful moment to open it.

Some authors I struggle to read, they’re so good. Pages and paragraphs are long meditations. Lately it’s Annie Dillard. We have this collection of Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, An American Childhood, and The Writing Life in one book. A few days ago I was somewhere with it reading An American Life. I relished reading about Dillard’s mom, with her childlike joy for the sounds of certain words, like “portulaca,” “poinciana,” and “Terwilliger bunts one,” as well as her artistic (and I would add adult) sense of duty toward form. Today, I thank Dillard for my meditation. Here’s how The Writing Life begins:

“When you write, you lay out a line of words. The line of words is a miner’s pick, a woodcarver’s gouge, a surgeon’s probe. You wield it, and it digs a path you follow. Soon you find yourself in new property. Is it a dead end, or have you located the real subject? You will know tomorrow, or this time next year.”

Tomorrow or next year. Like you have been digging all that time. And nothing but more cave ahead. The idea works for drawing, too. Whatever makes that possible is very interesting. She is using one medium to talk about something even larger than writing, per se (or drawing). She’s located the foundation under art and life. This, to me, is an amazing accomplishment, worthy of mention. By virtue of this multivalence, or what theologian David Tracy would call an “excess of meaning,” she’s articulated that how art works is how life works.