The nature of the will is one of the major problematics of life. Philosophers and artists have long labored to clarify the position we are in concerning the will. How much power does one person have? How much responsibility does one have in achieving for oneself the good life, and how can this be extended to others? How exactly are we situated in this world? To better understand the nature of will, artists, philosophers, and children open themselves up to opposition by treating it with a sense of play.

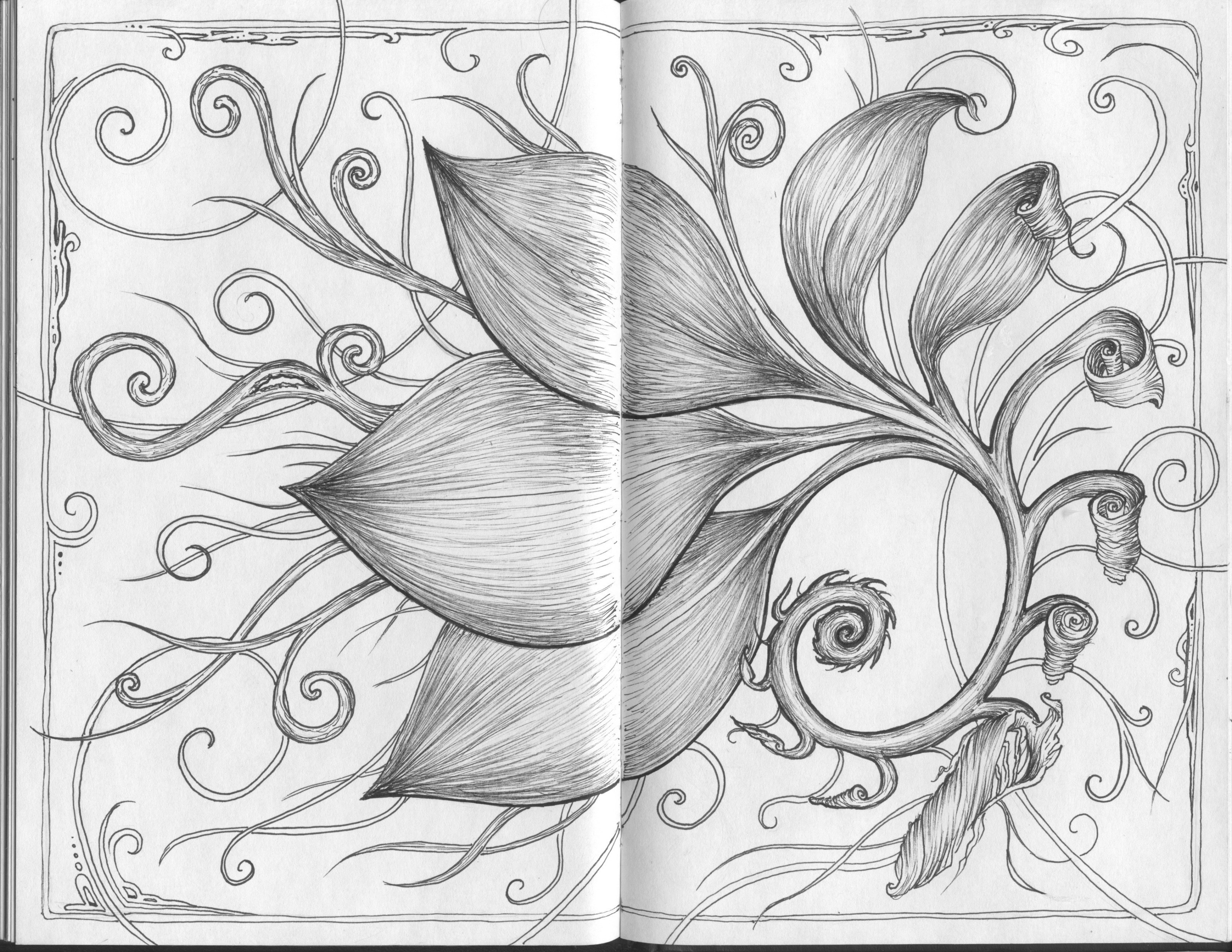

The child at play gives form to conflict, practicing “out in the open” in order to internalize what has been noticed in the external world, to gain understanding of self and situation. The forces driving conflicts between people are usually invisible, ideological, and unconscious, but once they are driving behavior, the child becomes aware yet lacks understanding. To develop a working model, or what Edith Cobb called a “world image,” the behavior is reproduced in experimental play.

Philosophers routinely reflect and do their thinking by surveying both sides of a problem. Socrates is the archetype for this. In his dialogues we often find Socrates asking questions normally thought to have obvious answers, questions like, “Do I want what is good?” As part of a chain of questions that bring the other’s inconsistencies of thought into higher resolution, he is surprisingly effective. Socrates often leaves his company in a state of shock from having lived so long under the aegis of certain beliefs and values without examining them.

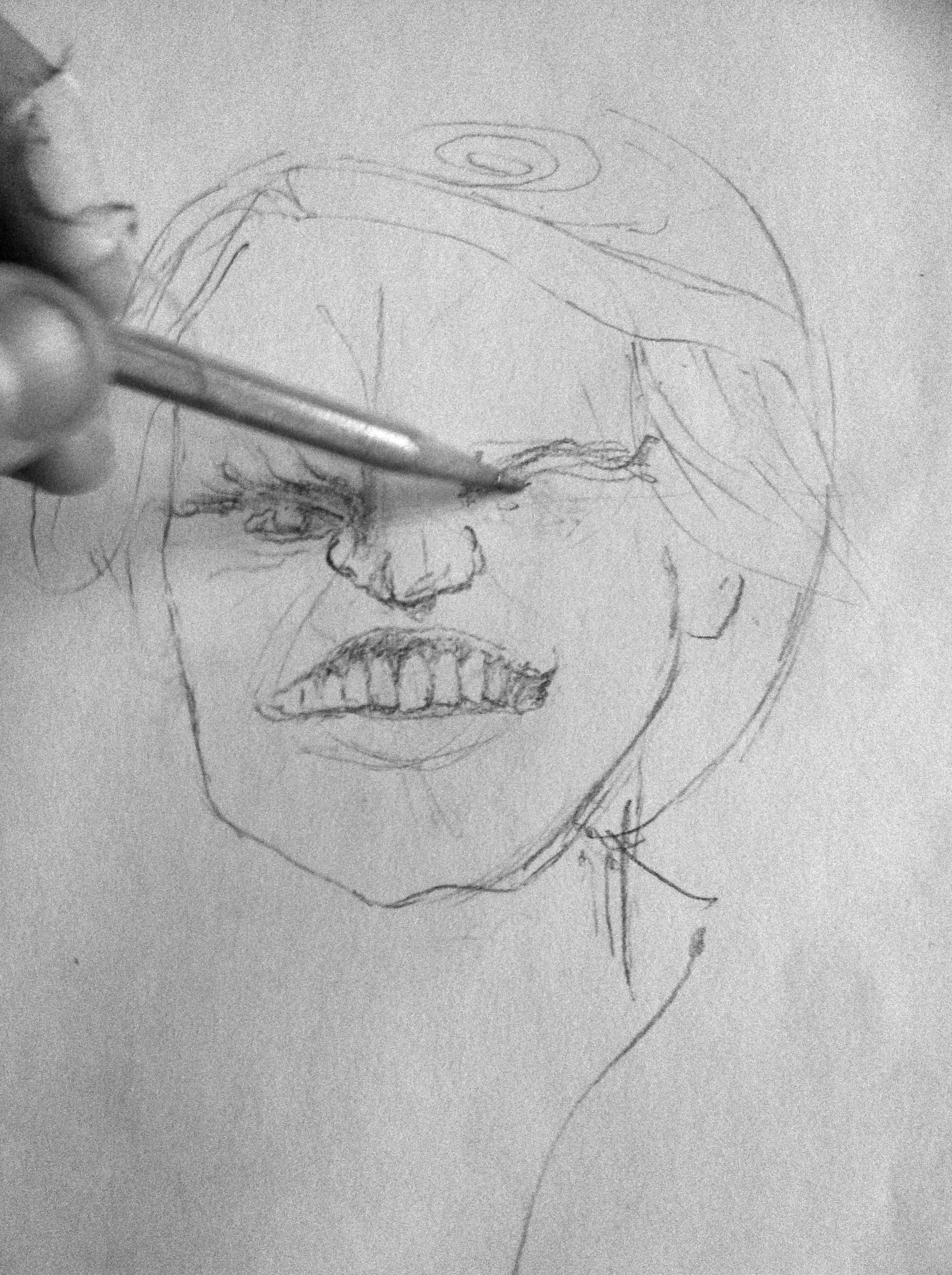

Similarly, artists often present situations without explicitly taking a side. In crafting a story, an author takes all the time that’s required for viewers to believe and situate themselves in the whole driving conflict. In order to do this, they must give equal weight to opposing sides. Good is labored equally to evil. This cannot be understated. Evil is not run away from. The author must take a detached stance to good as well as evil, and the long process of crafting such a story is a redemptive process for the author, for in that time love has been taken to evil. The work is finished; now the conflict is felt by the reader, in all its natural complexity. And this is what the work offers that life tends not to: honor to the paradoxical complexity of living.

The feeling of conflict is not going to be novel for anyone. Life is difficult, long, a labyrinth. No map could ever be created that would give absolute lasting order to the world, whereby we could determine what to do or where to go next. What is unique to the arts is that they offer safe passage through experience, and thus to transformation. In other words, the arts offer the best simulacrum of such a map. Life is always giving us experience; too often we fail to travel through it. Whether from anxiety or what Kierkegaard called the “dizziness of freedom,” fear or sheer confusion, we seem resistant to understanding or processing what happens to us. Such resistance promotes undesirable thought and behavior loops. If we would travel through experience, our transformation would be the effect. In order to do this, we must sometimes come down from the clouds of our own cleverness and righteousness and ground ourselves in earthly silliness. There are many compatible modes of being. There is no going out of character. To quote Walt Whitman,

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)